Advertisement

David Swanson is the author of the new book The Monroe Doctrine at 200 and What to Replace It With.

The Monroe Doctrine was first discussed under that name as justification for the U.S. war on Mexico that moved the western U.S. border south, swallowing up the present-day states of California, Nevada, and Utah, most of New Mexico, Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. By no means was that as far south as some would have liked to move the border.

The catastrophic war on the Philippines also grew out of a Monroe-Doctrine-justified war against Spain (and Cuba and Puerto Rico) in the Caribbean. And global imperialism was a smooth expansion of the Monroe Doctrine.

But it is in reference to Latin America that the Monroe Doctrine is usually cited today, and the Monroe Doctrine has been central to a U.S. assault on its southern neighbors for 200 years. During these centuries, groups and individuals, including Latin American intellectuals, have both opposed the Monroe Doctrine’s justification of imperialism and sought to argue that the Monroe Doctrine should be interpreted as promoting isolationism and multilateralism. Both approaches have had limited success. U.S. interventions have ebbed and flowed but never halted.

The popularity of the Monroe Doctrine as a reference point in U.S. discourse, which rose to amazing heights during the 19th century, practically achieving the status of the Declaration of Independence or Constitution, may in part be thanks to its lack of clarity and to its avoidance of committing the U.S. government to anything in particular, while sounding quite macho. As various eras added their “corollaries” and interpretations, commentators could defend their preferred version against others. But the dominant theme, both before and even more so after Theodore Roosevelt, has always been exceptionalist imperialism.

Many a filibustering fiasco in Cuba long preceded the Bay of Pigs SNAFU. But when it comes to the escapades of arrogant gringos, no sampling of tales would be complete without the somewhat unique but revealing story of William Walker, a filibusterer who made himself president of Nicaragua, carrying south the expansion that predecessors like Daniel Boone had carried west. Walker is not secret CIA history. The CIA had yet to exist. During the 1850s Walker may have received more attention in U.S. newspapers than any U.S. president. On four different days, the New York Times devoted its entire front page to his antics. That most people in Central America know his name and virtually nobody in the United States does is a choice made by the respective educational systems.

Nobody in the United States having any idea who William Walker was is not the equivalent of nobody in the United States knowing there was a coup in Ukraine in 2014. Nor is it like 20 years from now everybody having failed to learn that Russiagate was a scam. I would equate it more closely to 20 years from now nobody knowing that there was a 2003 war on Iraq that George W. Bush told any lies about. Walker was big news subsequently erased.

Walker got himself the command of a North American force supposedly aiding one of two warring parties in Nicaragua, but actually doing what Walker chose, which included capturing the city of Granada, effectively taking charge of the country, and eventually holding a phony election of himself. Walker got to work transferring land ownership to gringos, instituting slavery, and making English an official language. Newspapers in the southern U.S. wrote about Nicaragua as a future U.S. state. But Walker managed to make an enemy of Vanderbilt, and to unite Central America as never before, across political divisions and national borders, against him. Only the U.S. government professed “neutrality.” Defeated, Walker was welcomed back to the United States as a conquering hero. He tried again in Honduras in 1860 and ended up captured by the British, turned over to Honduras, and shot by a firing squad. His soldiers were sent back to the United States where they mostly joined the Confederate Army.

Walker had preached the gospel of war. “They are but drivellers,” he said, “who speak of establishing fixed relations between the pure white American race, as it exists in the United States, and the mixed, Hispano-Indian race, as it exists in Mexico and Central America, without the employment of force.” Walker’s vision was adored and celebrated by U.S. media, not to mention a Broadway show.

U.S. students are rarely taught how much U.S. imperialism to the South up through the 1860s was about expanding slavery, or how much it was impeded by the U.S. racism that did not want non-“white,” non-English-speaking people joining the United States.

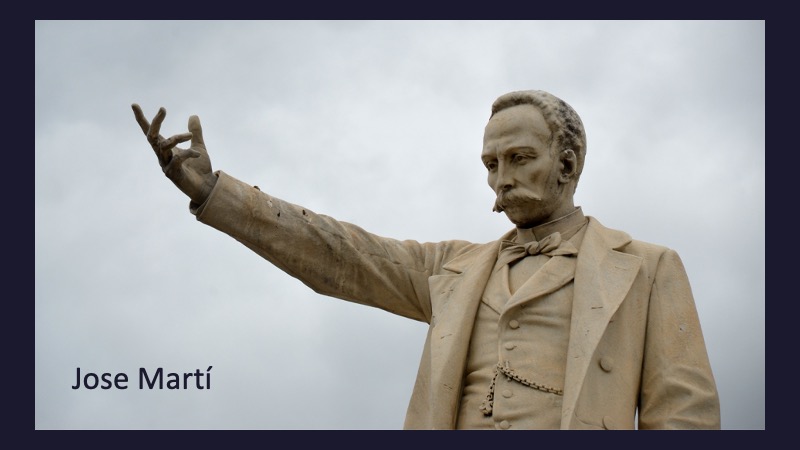

José Martí wrote in a Buenos Aires newspaper denouncing the Monroe Doctrine as hypocrisy and accusing the United States of invoking “freedom . . . for purposes of depriving other nations of it.”

While it’s important not to believe that U.S. imperialism began in 1898, how people in the United States thought of U.S. imperialism did change in 1898 and the years following. There were now greater bodies of water between the mainland and its colonies and possessions. There were greater numbers of people not deemed “white” living below U.S. flags. And there was apparently no longer a need to respect the rest of the hemisphere by understanding the name “America” to apply to more than one nation. Up until this time, the United States of America was usually referred to as the United States or the Union. Now it became America. So, if you thought your little country was in America, you’d better watch out!

David Swanson is the author of the new book The Monroe Doctrine at 200 and What to Replace It With.

Shared from: https://worldbeyondwar.org/the-monroe-doctrine-is-soaked-in-blood